In a 14-minute video posted to her YouTube channel, Kai Michelle wears a hot pink dress and demonstrates to viewers how to inject Ozempic, a prescription weight-loss drug.

Speaking to viewers from her kitchen, she talked about side effects like stomach cramps, but said she'd lost 20 pounds in 12 weeks and some days had no appetite at all.

“I've been trying to lose weight my whole life,” she told viewers. “I just want to lose weight and get to a size that I'm comfortable with.”

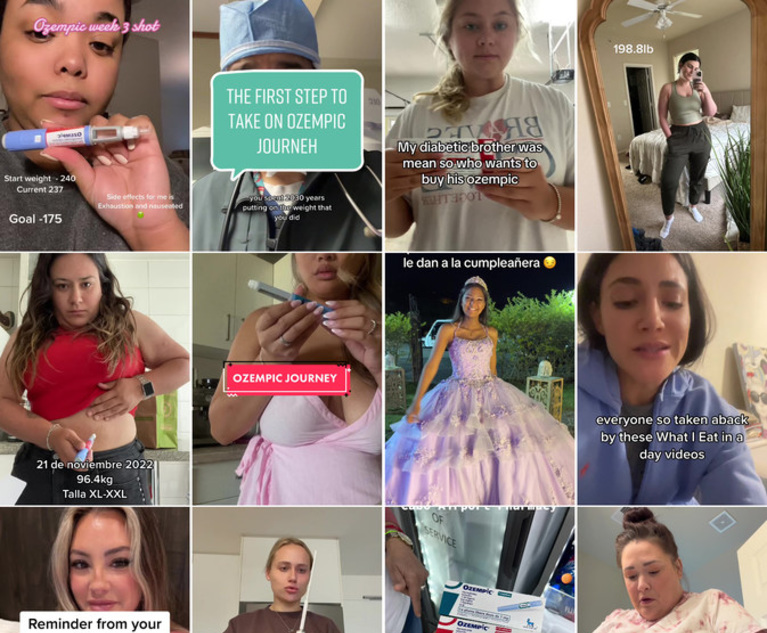

Social media marketing of Ozempic and related drugs, developed to treat diabetes and also used for weight loss, is a key part of the lawsuits against pharmaceutical companies Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly & Co. Advertising has proliferated on sites such as YouTube and TikTok, often in the form of personal testimonials, and paid influencers have boosted the drugs' popularity.

This is what makes Ozempic stand out from most other medications.

“I can't sit here and come up with anything that even comes close to this,” Sarah Couch of Motley Rice told Law.com. “The real power of social media is that it's incredibly customizable and incredibly present. Patients and potential consumers are getting these messages multiple times a day. It's not just once in a doctor's office or a once-a-day TV ad.”

The lawsuit alleges that Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly failed to adequately warn about the risk of gastroparesis, which can lead to nausea, vomiting and often hospitalization. Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly deny the allegations, saying the label contains warnings about gastrointestinal problems, but plaintiffs' lawyers argue that the disclosures downplay the seriousness of the risks.

But at the heart of the lawsuit is the promotion of drugs on social media.

“This is going to be a big focus for the prosecution in this case,” Brad Honnold, a partner at the Overland Park, Kansas, law firm Gonza Honnold, told plaintiffs' attorneys during a Feb. 9 webinar on the Ozempic litigation.

“Lots of misleading content from third parties”

More than 70 lawsuits have been filed over Ozempic and Novo Nordisk's other weight-loss drugs, Wegovy and Rebelsus, as well as Eli Lilly's Trulicity and Maunjaro, but lawyers expect at least 10,000 lawsuits to be filed.

U.S. District Judge Gene Platter for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Photo provided.

U.S. District Judge Gene Platter for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. Photo provided.U.S. District Judge Jeanne Platter, who is overseeing the multidistrict litigation for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, held an initial hearing Thursday.

While social media and online advertising for prescription drugs is nothing new, Ozempic and related drugs have taken the trend to a new level, especially with telehealth providers such as Noom and Calibrate sending the medication directly to patients' homes or local pharmacies.

Honnold told Law.com that this was “the first example of ultra-aggressive marketing” in both the social media sphere and the telehealth sphere, which has become widespread during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This is right up there with patient exploitation,” Honnold told Law.com. “This is technically the kind of encounter you have when you 'friend' someone on social media — a phone call, a very brief face-to-face meeting with some of them, a TV video — and is a world away from when a patient receives this information from their doctor in a timely manner.”

Couch, of Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, said actual informed consent isn't being obtained from patients who are eligible to receive the medication within five to seven minutes.

“Their only goal is to get as many subscribers as possible,” she told Law.com.

She said the lawsuits are aimed at uncovering potential financial ties between telehealth providers and pharmaceutical companies.

In a statement, Novo Nordisk acknowledged that its medicines are advertised on social media but insisted that influencers do not post content on the company's behalf.

“Patient safety is a top priority for Novo Nordisk, and we work closely with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to continually monitor the safety profile of our medicines,” the company said. “We acknowledge that there is a lot of misleading content on social media from third parties promoting prescription medicines, much of it from medical spas, clinics, telemedicine companies and social media influencers.”

Novo Nordisk said in a statement that it identifies and labels content on social media and does not work with influencers to share personal experiences.

In a separate statement, Eli Lilly said it does not provide its medicines or their ingredients to third parties.

“At Lilly, we are committed to acting ethically and responsibly in all we do,” the statement said. “The same is not always true for some companies advertising on social media. We encourage people to verify trusted sources before responding to specific ads on social media.”

“These drugs are not without risks.”

The use of telehealth providers and websites that aren't transparent about the risks means patients may not be giving informed consent, potentially opening the door to liability for drug companies, said Tara Scholar, a professor at the University of Arizona James E. Rogers School of Law who is following the Ozempic litigation.

“In a nutshell, the involvement of telemedicine and online weight loss platforms in prescribing and promoting these drugs can lead to complex legal matters for pharmaceutical companies, especially if they do not follow proper patient screening and monitoring protocols as these drugs are not without risks and can cause harm to patients,” she said.

Courts aren't the only place to scrutinize social media advertising for pharmaceuticals.

Sen. Richard Durbin (D-IL). Photo by Diego M. Radzinski/ALM

Sen. Richard Durbin (D-IL). Photo by Diego M. Radzinski/ALMLast month, Democratic Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois and Republican Sen. Mike Braun of Indiana called on the Food and Drug Administration to crack down on “misleading social media advertising” of prescription drugs, particularly those targeted at children. In their Feb. 14 letter, they mentioned Ozempic.

“The power of social media and the proliferation of misleading advertising means that many young people are taking medical advice from influencers rather than medical professionals,” the researchers wrote.

But it's not just the supply method and the age of patients that are of concern: Sklar said online advertising for the drug can be misleading, emphasising its benefits over its risks.

“Social media promotion for Ozempic and Wegovi has been extensive and aggressive, including the use of influencers and celebrities in ads on TikTok, Facebook and Instagram, and appears to target a much broader demographic than traditional pharmaceutical advertising,” she said. In addition, more weight-loss drugs are expected to hit the market. “All of this, combined with the high cost of the drugs, raises alarm bells for strict restrictions on pharmaceutical advertising,” she said.