Changing technology has given mailbox providers more control over everything from message design to retention periods, putting email marketers on the losing end of the battle for inboxes.

Marketers have never had 100% control over how their email messages appear in email clients. Right now, I'm tracking four changes that take away even more control over messages and how recipients see and act on them. Some are born out of the application of artificial intelligence, but others are driven by user privacy, inbox clutter, and even climate change.

If you’re still sending emails like it’s 1999, or even 2019 or 2021, your email program could be affected in some way unless you update your practices.

These changes aren't all bad, but each one is a signal that we must re-understand what's happening, what it means, and how to reshape our strategies and programs in response.

4 email changes that will transform your inbox

There's a lot going on in email right now that has nothing to do with generative AI. Here are four trends I'm tracking right now:

1. Cluttering Apple's Inbox Again

Apple's Mail Privacy Protection (MPP) feature, introduced in 2021, was the first warning to inboxes, with Apple attempting to protect subscriber privacy by hiding when, where, and even whether subscribers opened email messages.

After the initial shock wore off, we as email marketers figured out how to make up for that data loss and got back to business as usual: communicating with subscribers and customers who opted in to receive our emails.

Three years later, Apple Intelligence (yes, that's “AI”) is coming to the native Apple Mail client with iOS 18, the next system upgrade for iPhone 15 and beyond. One feature to look out for is Apple Intelligence's “Personal Intelligence” feature, which uses AI to categorize messages into tabs, similar to Gmail's tab system.

Apple explains: “On-device classification organizes and categorizes incoming emails into 'Primary' for personal and time-sensitive emails, 'Transactional' for confirmations and receipts, 'Updates' for news and social notifications, and 'Promotions' for marketing emails and coupons. Mail also features a new Digest view that brings together all relevant emails from your business, giving users a quick look at the emails that matter to them.”

As long as you're sending messages that your subscribers have requested, opened, and acted upon, it's not all bad. It's unclear whether Personal Intelligence will sort messages by sender or date within each tab, so we'll wait to see how the new system works when it goes live later this year.

The advent of the marketing-focused “Promotions” tab has rekindled concerns that marketing emails will get lost if they're not in the “Primary” tab or “Priority” view. I know this isn't a huge drawback in Gmail, so I'll classify this as something to be aware of.

One potentially positive development is grouping messages by sender. When applied to promotional or marketing messages, you might find branded emails that subscribers are retaining for transactions or follow-up actions. (See the second and third bullets below for trends that may work against this benefit.)

Apple is introducing AI-generated summaries of message content, a feature that has existed in the Yahoo Mail app for years but has been inconsistent: some email summaries are detailed, others just list the sender's name, and image-based emails in particular have no summaries.

None of these changes mean the end of email or affect how your email looks or functions. However, be aware that you now have even less control over the inbox and how your subscribers access it. To ensure that your subscribers find your messages in their inboxes, you need to make your messages more relevant and engaging.

2. Expired emails

The Email Expiration Date project advocates automatically deleting old emails to reduce the energy and data storage required to store them. Reducing email's carbon footprint is certainly a noble goal, but we need to be careful about how we use email.

While deleting marketing emails in bulk seems like a great idea with a smaller carbon footprint than a “Sounds good for me!” reply confirming dinner with a friend, you need to be mindful of email deletion deadlines so as not to undermine one of email’s great benefits.

The benefit is that subscribers tend to save emails from brands they trust and buy from regularly, and search for those brands when they want to buy again.

Many enterprise email services routinely delete emails regardless of engagement unless the recipient changes their settings. However, email expiration could be a catastrophe for commercial senders if it becomes an arbitrary limit imposed by mail transfer agents and mailbox providers. That doesn't seem likely, according to project advocates, because senders, ESPs, and mailbox providers would need to work together to make this process successful.

However, senders need to think strategically when choosing their “expiry date” to ensure that customers don’t intentionally delete stored emails, thereby eroding their long-term value.

Deeper dive: 3 keys to increasing email engagement with Gmail

3. Unsubscribe prompt after 30 days

Need a boost to send emails to new subscribers ASAP instead of whenever you want? Give us a try!

Google and Yahoo now require senders to include a 30-day unsubscribe feature in their email headers as a condition of inbox delivery, which disrupts normal email relationships in three ways:

- If you don't send an email within 30 days of opting in, new subscribers will be prompted to opt out before you send them their first email.

- The 30-day opt-out prompt is intended for people who have had no engagement during that time, but I still see this prompt in emails from senders I deal with regularly.

- Emails can have a long shelf life: the DMA UK Consumer Email Tracker 2023 lists “save the email for later” as the third most common action consumers take when receiving an email that interests them. This forced opt-out breaks the habits consumers have built up over years.

The unlist header feature is not new. Senders have been inserting unlist functionality into email headers to allow users to unsubscribe from messages instead of using an unsubscribe link or button in the message. This isn't a bad thing if it encourages inactive subscribers to opt out instead of hitting the spam button or simply remaining silent.

A suggestion from my email colleague Chad S. White (Oracle Digital Experience Agency) is that extending your opt-out period prompt from 30 to 90 or 120 days may give you enough time to prove your value. The prompt will appear in your email (inbox and header for Gmail, footer for Yahoo), but by that time your subscribers may be less likely to act on it.

You may have noticed that the inboxes of some email clients now include more than just the sender name, subject line, preheader, and date. Some emails now include graphics, calls to action, and even offer codes that are pulled into the inbox from the email content.

Two emails arrived in my Gmail inbox recently. One shows a harmless application of what Gmail calls “auto-extraction” using annotations (see Gmail's instructions) and Schema markup, which you can use to add quick actions to your inbox view. The other, not so much.

SmarterTravel inbox images are the first images displayed in your email. They relate directly to the subject line and intent of your message. They enhance the inbox view and motivate recipients to open your message.

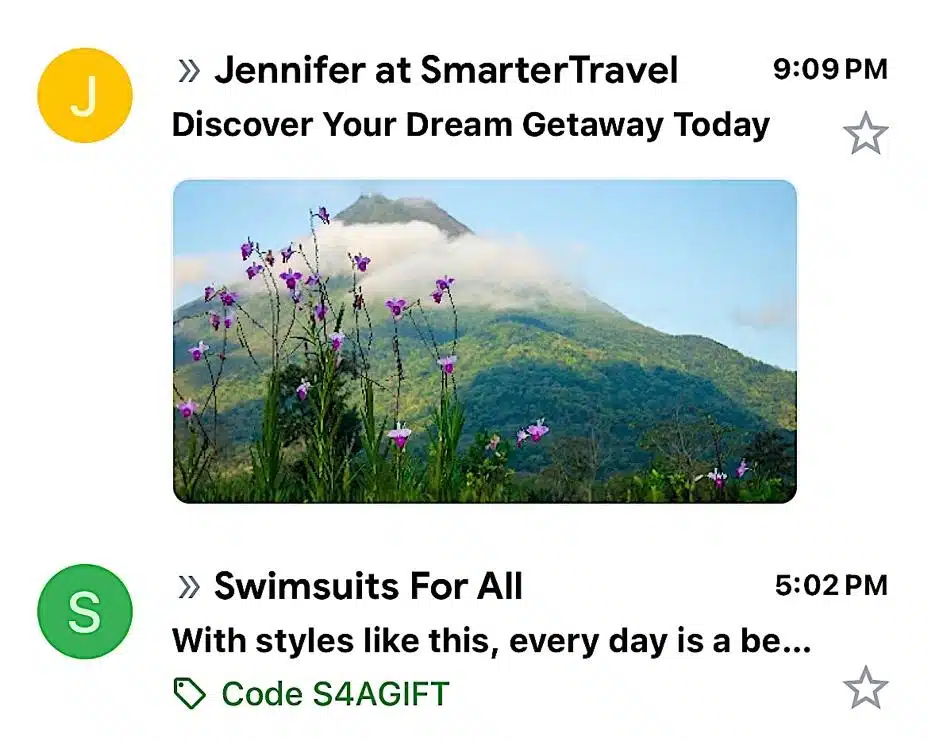

The promo code in Swimsuits for All's emails is written after the preheader, but not part of it. The code appears only once in the email, embedded in an image that has “Shop Now” as alt text. There is no mention of the code, and although it appears on the brand's website, I had to hunt for it twice to find it in the email.

Was that done intentionally, or did Gmail choose to extract it and display it?

I agree with White, who is particularly vocal in his opposition to automated extracts, which rewrite emails for their own purposes and may not reflect what a brand wants to achieve with the email. As White says, it raises the question of who owns the preview content in an email: the brand or the inbox provider?

The promotion that appeared in the inbox was likely intended as a reward for customers who opened and clicked on the email. Once the code was in the inbox, customers could copy it and go directly to your website, bypassing the email and taking it out of the engagement and attribution equation.

One ignored email changes nothing. But Gmail has a wide reach, and Swimsuits for All is a big brand, which means potentially thousands, or even thousands, of lost clicks and opens that Gmail itself uses to measure engagement, and interactions that the brand uses to measure both engagement and the effectiveness of its campaigns. Sure, the brand wins the sale, but email takes another hit.

Read more: New rules for mass email senders from Google, Yahoo: What you need to know

Don't ignore the effects of seemingly small changes

None of these trends will spell the end of email, but each one is game-changing enough that marketers need to act or risk losing email's effectiveness.

Email senders have always known they had no control over how email clients displayed their messages. These changes are now impacting the inbox, where marketers had control over what information was displayed. Both of these trends are slowly diminishing that control.

None of this is new or unexpected: Email marketers have always had to deal with changes made by mailbox providers to keep commercial messages out of inboxes, even though they claim they're only doing it to please their customers and users.

Any time we as email marketers face an obstacle, we complain about it, and then we roll up our sleeves and come up with a workaround or team up with smart people to turn the problem into an advantage. Now is the time to do that again.

Contributors are invited to create content for MarTech and are selected based on their expertise and contributions to the martech community. Contributors work under the supervision of our editorial staff, and their contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. Any opinions they express are their own.