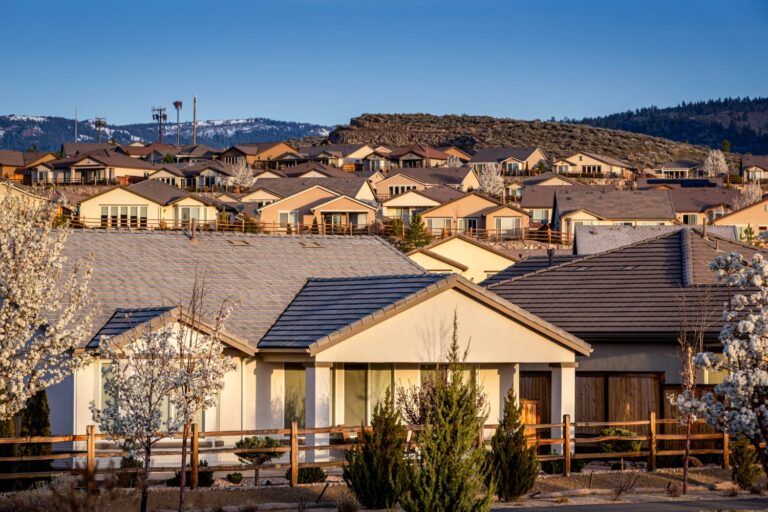

At 31 years old, Kashmir Martin would like to move into her first home and start a family with her husband in Reno, Nevada — part of a critical swing county in a swing state that’s expected to have a central role in the upcoming presidential election.

But despite her salary doubling since the start of the pandemic and the couple now making more than $200,000 a year, Martin says she’s feeling locked out of the dream of homeownership after prices in the region have jumped nearly 50% since 2019.

It’s not for lack of trying. Martin has looked at more than 100 homes, on some weekends going to more than more than 20 open houses. But even at the top of her $550,000 budget, most of the homes she has found would require extensive repairs she can’t afford, including sinking foundations, damaged sewer lines, 20-year-old roofs, and windows from the 1960s. One house was in such disrepair the lenders weren’t willing to finance it.

After about two years of searching, Martin says she has all but given up — and put on hold plans to have a baby until she can afford to buy a home.

“Seemingly, on paper, I’m making more money, I’m doing better,” Martin said. “But I feel less financially secure than I did back in 2015 when I had just barely graduated college and was a first-year accountant.”

Purchasing a home has grown increasingly out of reach for millions of Americans over the past three years — with little indication of the situation improving, according to the NBC News Home Buyer Index, a unique analysis that measures the difficulty of buying a home in America based on price, housing supply and the competitiveness of a market. Home prices have far outpaced middle-class incomes, mortgage rates are at their highest levels in more than two decades, and fierce competition among buyers has 3 out of 10 homes selling above their listing price, according to data from Redfin.

In Washoe County, where Reno is the largest city, that financial pressure from the housing market could have wider implications for how voters feel about the economy. As prices surged faster than wages, the county ranked in the top 200 out of 1,300 measured when it comes to the difficulty of buying a home, according to the NBC News index.

“Housing affordability is a massive issue,” said Mike Noble, CEO of Noble Predictive Insights, a polling and research firm that focuses on Nevada and other Southwestern states. “Housing is coming up everywhere in polls. It’s a huge burden on cost of living. A big part of why inflation is so painful is that people can’t afford housing — it shows up in multiple places in every poll.”

Washoe County is one of the few swing spots on the deeply divided Nevada electoral map, where voters in the Las Vegas area swing heavily for Democrats and those in the vast rural parts of the state widely favor Republicans.

The county has seen strong economic growth under President Joe Biden. Average weekly wages in Washoe County, while lower than the national average, have increased 27% since 2019, faster than wages nationwide, and the region’s labor force has also grown at a more rapid clip. While unemployment has ticked up in recent months, it was at a near-record low in 2022 and has been hovering close to the national average.

But with that growth has come a spike in housing costs that is putting a strain on households across the income spectrum. In Reno, the increases have been driven by a number of factors, including a wave of new residents in 2021 from California, who had the ability to work remotely and were drawn to the region’s lower taxes and housing costs, according to local researchers, realtors and government officials. Those California buyers brought with them higher West Coast wages and all-cash offers after selling their more expensive Bay Area homes, driving up prices above what many local buyers could afford.

‘I’m falling a little behind’

In Washoe County, single-family home prices have increased 46% since 2019 to $580,000, according to data from the Washoe County Assessor’s Office. That would amount to a $3,000-a-month mortgage payment, not including taxes and insurance, at current interest rates of around 7% and with a 20% down payment. To afford that home, a household would have to make more than $100,000 a year, well above the current median household income of $80,000.

In 2019, the mortgage payment on a typical home in the area would have been $1,800 when interest rates were around 4% and the median home sale price was around $400,000. That payment would have been considered affordable for a household making around $65,000 a year — below the median household income of $72,000 in 2019.

For renters, the situation isn’t much better. Among those in the Reno area, more than half were paying over 30% of their income on rent and utilities, according to data compiled by Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

Martin, who works as an accounting manager for a mining company, has seen her salary more than double to $140,000 a year since the start of the pandemic. Still, she says she’s been unable to find a home with a mortgage payment of under $3,000 a month, the maximum amount she feels she can afford given future costs she anticipates from child care and possible fluctuations in her husband’s salary.

Most of the homes she’s looked at in that price range are around 1,500 square feet with three bedrooms and built between the 1940s and 1980s in the Old Northwest or Old Southwest Reno neighborhoods. Moving to some of the more affordable parts of the region farther north could add 45 minutes to her husband’s daily commute, which is already an hour each way.

At the current interest rate of around 7.5% that Martin has been given, she couldn’t even comfortably afford to buy her childhood home, which her parents bought decades ago on their salaries as a teacher and a casino worker. But despite doing well in school, choosing a well-paying profession and working hard to advance her career, Martin says she feels like she isn’t any better off financially than her parents were at a similar stage of life.

“I’ve taken all of the steps that I thought I would need to take so that I could do better than my parents,” said Martin. “But I kind of have this feeling that I am not getting ahead. If anything, I’m falling a little behind.”

That’s left her and her husband, who makes roughly $65,000 a year as an audio technician, continuing to rent a townhouse in Reno for $2,300 a month. If she were to buy the equivalent property, she estimates her mortgage payment would be $3,700 a month.

Martin said the struggle in trying to buy a home has made her more inclined to vote for candidates who support labor unions, which she thinks will help increase wages so more people can afford a home at the current prices.

“From a federal level, anything that can help increase wages and get people good, high-paying jobs is going to help this situation,” she said. “I just don’t foresee prices coming down.”

Vice President Kamala Harris, the de facto Democratic presidential nominee, has advocated for increased funding for affordable housing, tax credits for first-time homebuyers, and a cap on rent increases tied to tax incentives for landlords during her time in the White House.

Republican nominee Donald Trump’s campaign has said he would lower housing costs by encouraging the construction of new housing on the peripheries of cities and suburban areas where land is cheaper and roll back “anti-suburban housing regulations.” As president, Trump spoke out against building lower-income housing in suburban areas, painting a dystopian vision of low-income housing in the suburbs.

But neither party has made talking about the issue of housing a top priority — like immigration, climate change and abortion have been — making it unclear who comes out on top on the issue in November, said Noble.

“Since it’s basically a new issue, neither party has figured out how to dominate it,” he said. “Both parties are still fleshing out messages.”

‘Not the world we live in’

For those who have purchased a home in the Reno area despite the high prices and interest rates, the cost can cause a significant financial strain.

Like Martin, Philip Chavez has also seen his wages jump since the start of the pandemic, but that hasn’t eased his financial worries. A year ago, Chavez was making $20 an hour working in a GM parts distribution center in Reno and renting a small two-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment that he shared with his wife and children, ages 4 and 12.

After last year’s United Auto Workers strike, he saw his pay increase to $36 an hour. Now, with overtime and profit-sharing, Chavez is expecting to make around $100,000 a year. For the first time, he was able to qualify for a mortgage that would enable him to buy a home in the city where he’s lived for nearly two decades.

“That increase was the only reason why I was able to even start looking in any capacity. There was no way I was going to get a house on $20 an hour,” he said. “After the raise we got after the strike, it was the first time I felt like I was able to breathe.”

Though Chavez was recently able to purchase a home for $470,000, his monthly mortgage payment of $3,700 a month accounts for about half of his take-home pay. That’s left his family continuing to be on a stretched budget despite making far more than the area’s median income and buying a home below the median price.

“I am really praying for rates to go down so I can try to refinance quickly, because it’s a big payment. It’s a good portion of my income for now,” said Chavez. “It’ll be a little lean here and there, but, you know, I’ll eat less or something. We’ll figure it out.”

Politically, Chavez said he doesn’t see Republicans putting the economy on any better of a footing and thinks Harris is an improvement over Biden as the nominee in the upcoming election. Chavez said he remembers Harris walking the picket line with him and his colleagues in Reno during the 2019 UAW strike.

“If we want to have a country like it is now or make it better, we’re not going to do it by voting Republican,” Chavez said. “Trickle-down economics doesn’t work, because trickle-down economics relies on a benevolent person trickling it down, and that’s not the world we live in.”

‘You’re not going to find anything’

At current home prices and interest rates, the average wage worker in all but two industries — information services and financial activities — is unable to afford the median-priced home in Washoe County, according to data compiled by Brian Bonnenfant, project manager for the Center for Regional Studies at the University of Nevada, Reno. That includes many working in the hospitality industry, which is the county’s largest employer with a median wage of $16 an hour plus tips, according to data from Bonnenfant.

“Working-class folks, they are getting squeezed out of the housing market, and rents are through the roof, and there’s a lot of abuses that haven’t been curbed,” said Ted Pappageorge, secretary-treasurer for Nevada’s Culinary Workers Union, which represents 60,000 workers in the restaurant and hospitality industry. “I think with the political class out there, they are not taking this on as aggressively as they need to. We see some stuff from the Democrats on housing, but it’s just got to be much more aggressive.”

Local officials said housing has become the No. 1 issue they are hearing about from voters and they are working to provide relief, especially to some of the area’s lowest-income residents. The Reno City Council has approved funding or incentives to help add more than 4,300 affordable units over the past seven years.

Still, the city needed an additional 21,000 affordable housing units to meet demand as of the end of 2022, according to Nevada’s last housing progress report. The Reno Housing Authority has more than 3,000 households on its waitlist for federally funded housing vouchers that help low-income households pay for rent, and the number of people experiencing homelessness increased 4% this year to 1,760.

At the Food Bank of Northern Nevada, officials have seen a steady increase in demand since the pandemic even as wages have increased and more people have gone back to work, with rising housing costs a key factor cutting into budgets, said Jocelyn Lantrip, director of marketing and communications for the Food Bank of Northern Nevada. The number of people it is assisting has increased 15% since last year and 34% from two years ago.

“People have to pay their rent, and so they don’t buy as much food or they don’t have money to buy food, and that’s what we see a lot of,” said Lantrip.

Janine Cowie is among those struggling to navigate the city’s housing market on a lower income. Cowie was recently promoted to the role of behavior specialist at the child care center where she works — increasing her pay from around $17 an hour when she was working as a lead teacher to a salary of $45,000.

But while her pay has gone up, so has her rent. She now pays $1,700 for a two-bedroom apartment — more than half of her monthly take-home pay. It is a major strain for Cowie, who lost her husband to suicide in 2021 and is now the sole provider for her 2-year-old and 4-year-old children.

She recently started looking to purchase a home for $300,000 after being preapproved for a mortgage for that amount. But she came up empty-handed.

She said there were only a few homes available in that price range, all of which required significant home improvements she couldn’t afford.

“When I actually found a realtor, they were basically like, ‘You’re not going to find anything for the price around here,’” Cowie said.

She said her struggle to find housing has contributed to her leaning more toward a third-party candidate in the upcoming election. But she said she would be open to voting for Harris as she looks more into where the vice president stands on certain issues.

In the meantime though, she doesn’t expect to buy a home anytime soon.

“Unless you make a lot of money, I don’t see how anyone finds a place,” she said. “I’m almost 30 and all my friends are renting. I’m just kind of expecting to rent for a really long time.”